Nova Gorica, a phenomenon by the border

“We would like to build something big, beautiful and proud, something that would shine across the border,” said Prof. Edvard Ravnikar, creator of the first urban plan of Nova Gorica. However, in the end, the town was built according to the abilities of the people living in this part of Slovenia. A town which reflects the true image of its three-quarters-of-a-century: a town which is not a monument, but a vital and never completed town with a set of projects that need completion, upgrading, continuation and new ideas.

Bronze model of Ravnikar's Nova Gorica, photo: Katarina Brešan.

The idea for a new town was born in 1946, a good year after the end of World War II, when it was clear that a new border between Italy and Yugoslavia would cut off Gorica from its hinterland and that instead of the territorial integrity, two torsos would arise: the town of Gorica – a head without a body on the Italian side, and its hinterland Goriška – a body without a head on the Yugoslav side. The decision about building a new town that would substitute the lost Gorica was initially only a wish and a request of the Goriška inhabitants, but before long became a political project with which Yugoslavia would demonstrate the ability and will of the new social order to the »rotten« Western capitalism on the exposed edge of the then socialist block.

The new town was erected by the border so that it could merge with the “lost” Gorica someday in the future. Several proposals were submitted for it, and the architect Edvard Ravnikar proposed the winning solution: this was an urban design of a contemporary city, at that time the most modern European urban planning guideline, the main representative of which was the French-Swiss architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, known as Le Corbusier, under whom Ravnikar had trained before World War II.

The area on which the town sprang up had been a marsh and partially a devastated Gorica cemetery. Consequently, before starting to build the town, the terrain still needed to be prepared and ameliorated. The Yugoslav youth brigades (the town is alleged to have been a town of young people, a town of future to be built by the Yugoslav youth) started arranging the Koren brook, a duct of excess water from the future urban area, after a few months after the creation of the border, i.e. on 3 December 1947.

Regulation of the Koren stream in 1948. Source: PANG.

On 13 June 1948, the foundation stone was laid down for the first apartment block, which means that less than nine months passed from the first decision to build a town on Blanča (as the southern part of the present town used to be called) to the laying of the first foundation stone. During this period, the necessary financial resources were provided, the plans were drawn up and the mandatory basic infrastructure setting was set up: Today this is a hardly repeatable and admirable achievement.

Photo of building a block of apartments. Kept by: Goriški muzej.

All towns experience ups and downs, but Nova Gorica experienced its first fall right at the start. Almost overnight, the town was no longer in the political focus. With a dispute between Tito and Stalin in 1948, Yugoslavia made an enemy to the east and the West became its even more powerful ally and friend. As a result, the idea of shining across the border became uninteresting and the source of national funding for further building dried up. Everyone wanted to wash their hands of the town – a pre-term infant, incapable of independent life; in the end, care for the town fell on the inhabitants who desperately needed it in the light of political goals.

After this shock, Nova Gorica struggled to its feet, picking itself up with its own forces for fifty years, but experienced a new impetus in the middle of the sixties. The border, which was the reason why the town had arisen, mainly contributed to this. Its position on the border (at that time, they proudly claimed this to be the most open border in Europe, which was undoubtedly true at least on the line between East and West) offered the border area great opportunities for development, not only because of liberalised movement of goods but particularly because of the flow of ideas, import of the most advanced ideas from the West, which placed the industry of Nova Gorica at the forefront in several fields in the Yugoslav market, whereas its exports were mainly oriented towards the West. The healthy economy helped the town to rapidly grow and expand, the number of inhabitants rapidly increased and a succession of urgently needed regional facilities were built, such as a hospital, secondary schools, cultural facilities and the like. In the 1980s, when Yugoslavia was in political and economic crisis, this also had an impact on Nova Gorica, resulting in the slowing down and even demise of its development.

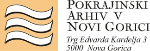

A view of Nova Gorica in the early 1950s. Kept by: Goriški muzej.

After Slovenia gained independence at the beginning of the 1990s, Nova Gorica was also overwhelmed with optimism. The feeling that they would soon become a part of a united Europe suffused the inhabitants and policymakers with a desire to upgrade the town, which got a new theatre, a library and a town pool … Its position on the border enabled Nova Gorica to become the largest gambling town in this part of Europe, which was not really welcomed by the majority of Nova Gorica inhabitants, aware as they were of the vulnerability of a strong monocultural economic direction.

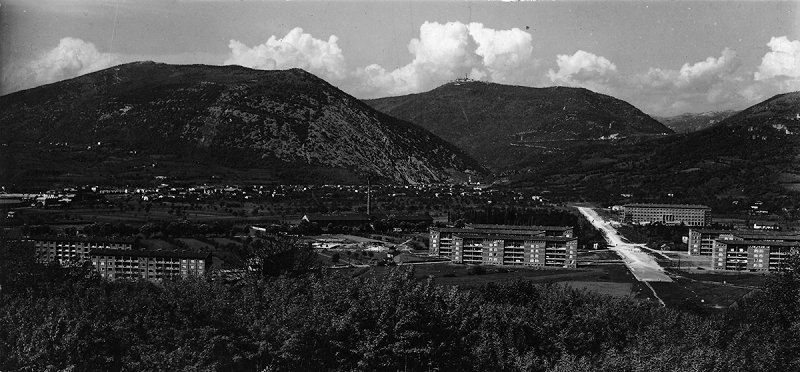

The view from the skyscraper on Kidričeva Street. Kept by: Goriški muzej.

The idea to join the towns on the border – Gorizia on the Italian border and Nova Gorica on the Slovenian side – was becoming increasingly attractive and realisable, leading to the question of how the towns could connect. Should they become one town or they should remain two, each with its own historical, urban and cultural characteristics, but connected in an indivisible whole like Siamese twins that could not be separated from one another.

The exceptional position by the border also inspired the idea that on 30 April 2004 Slovenia should enter the European Union on a symbolical level right here in Nova Gorica, on the square in front of the railway station, which the border divides into two equal parts, rearranged in a common ceremonial venue for events. The square with its symbolic mosaic is called Europe Square on the Slovenian side in memory of this event, and, at the same time, it is a symbol of the connection of the two towns.

Trg Evrope, photo: Katarina Brešan.

Thus, the area on the border, which appertained to no one for many years and which is located on the outskirts of both towns, started to acquire a symbolic role of connection and has become a decisive reason for the fact that Nova Gorica together with Gorizia won the title of European Capital of Culture for 2025. This will be the year when the two towns will connect and unite again through this once devastated area.

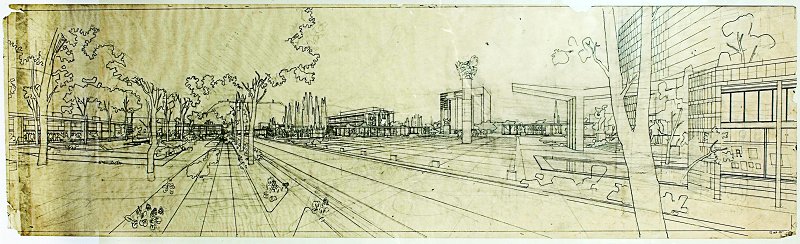

The development of Nova Gorica went its own way: it adjusted and also strayed from the original plan, from which only a model and a monument in the centre of the town remain. Is this good or bad? If we had followed the plan to the letter, there would now be even fewer buildings that reflect the time during which the town developed, or they might have built something that did not respond to the changed demands of modern living. Thus, we can observe the stratification and footprints of time; from the outside one can see what was built at the beginning or soon after the town’s conceptual design was realised, what was built in the seventies and what in the new millennium. As Prof. Ravnikar said: “Either the life of a town is eternal metabolism or there is nothing of that.” Despite this fact, its mark as well as the concept of the main town street – “Magistrala” or Kidričeva Street – has remained, which has still not been endowed with its envisaged image and function, but it will undoubtedly get it sooner or later.

Photo of Ravnikar’s perspective of the main town street – “Magistrala”. Kept by: MAO.

Tomaž Vuga, Nova Gorica urbanist, author of the book Project: Nova Gorica (Založba ZRC SAZU, 2018)